I have long known that I have the coolest father who ever lived. Sorry, those of you who may think your dads get that title, because my dad has been holding it tight since April 1976. I was prompted to think about this fact some more this afternoon, on my way from the village post office to the village coffee shop for lunch. As I came down the steps of our humble p.o., rueing the fact that I conservatively wore my winter coat even though it's about 60 degrees outside, I heard a motorcycle engine rev and backfire. I looked to my left and saw a couple coming down the road on a modest-sized Harley--not one of the big hogs, but big enough to make some noise in my tiny town. I grinned, and the woman holding on behind the driver unclasped her right arm and gave me a big wave.

I have long known that I have the coolest father who ever lived. Sorry, those of you who may think your dads get that title, because my dad has been holding it tight since April 1976. I was prompted to think about this fact some more this afternoon, on my way from the village post office to the village coffee shop for lunch. As I came down the steps of our humble p.o., rueing the fact that I conservatively wore my winter coat even though it's about 60 degrees outside, I heard a motorcycle engine rev and backfire. I looked to my left and saw a couple coming down the road on a modest-sized Harley--not one of the big hogs, but big enough to make some noise in my tiny town. I grinned, and the woman holding on behind the driver unclasped her right arm and gave me a big wave.

My father, you see, has harbored--and may still harbor--hopes of retiring from his career as an automotive innovator to the back of a Harley. He has hoped, against hope, to get my mom a sidecar so that they can go tooling around the country in mad biker style. I know he's not just talking the talk; he worked for a year or so at the local Harley-Davidson shop, helping repair bikes. He could not only rock the Harley but also fix it if it broke down.

But, Harley or no Harley, my dad rocks out.

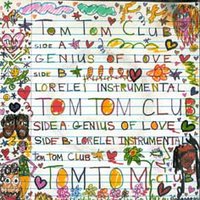

In November 1980, a little album called Autoamerican debuted. You can do the math and figure out how old I was when my dad found me on the green carpet in our blue living room and said, "Come hear this." We went into the family room and sat on the floor--on the same rug that's now in my own living room--and I listened for the first time to Debbie Harry's sultry croon: "Toe to toe, dancing very close..." And then, suddenly, just when I thought the song was, you know, just some song, came the break: "Fab Five Freddy told me everybody's fly..." And then--it just kept getting better--we were hearing about the Man from Mars, and he'd eaten our head, and we were eating up cars (Cadillacs, Lincolns too! Mercury, and Subaru!), and bars (where the people meet!), and then we stopped eating cars and eating bars, and then we only ate guitars! Get up!

In November 1980, a little album called Autoamerican debuted. You can do the math and figure out how old I was when my dad found me on the green carpet in our blue living room and said, "Come hear this." We went into the family room and sat on the floor--on the same rug that's now in my own living room--and I listened for the first time to Debbie Harry's sultry croon: "Toe to toe, dancing very close..." And then, suddenly, just when I thought the song was, you know, just some song, came the break: "Fab Five Freddy told me everybody's fly..." And then--it just kept getting better--we were hearing about the Man from Mars, and he'd eaten our head, and we were eating up cars (Cadillacs, Lincolns too! Mercury, and Subaru!), and bars (where the people meet!), and then we stopped eating cars and eating bars, and then we only ate guitars! Get up!

For someone whose musical taste had run to Free to Be, You and Me and Sesame Street (both of which I had in awesome vinyl that I spun on my FisherPrice portable record player like the DJ I'd still like to be, someday), this Blondie group was a revelation.

Things have just gotten cooler from there. At our first house in Indiana, we had six acres of wooded property, and so my father bought a used riding mower/tractor to use for cutting the lawn and vacuuming up leaves. Then, he also used it to cut an intricate network of trails through our property so that my brother and I could play in the woods without coming home covered in poison ivy or weird animal bites or woody abrasions. He kept the trails clear for us for the four years we lived in that house. I count them as one more reason my brother and I get along so well now; we spent a lot of youth-time running around making up stories and stuff, and, well, just running around. In those days, he drove a red Corvair, and then a big ol' Oldsmobile with a bass tube in the trunk (my brother can still rattle things with that bass tube, now that it's in his trunk), and he and my mom picked out an awesomely vintage Airstream trailer that we pulled behind the Malibu for years. This was years after he'd built a monster N-gauge train table in the basement, with a bridge and figure-eights. And that was years after he and my mom had let us draw with markers all over the drywall in the basement that was eventually going to get covered up with paneling anyway. (Note, those of you with children: I'm writing this stuff for you as much as for my dad.)

When my parents went out on their first date, on Bastille Day in 1967, my father's opening gambit was to hand my mother the button she had lost from her chartreuse leather coat months earlier. "Where did you get this?" she said. "My people are everywhere," he replied. Now you know how cool both my parents are. I mean, really: a redhead with a chartreuse leather coat? and a guy who manages to totally deadpan his way through giving a stranger back her lost button? I think my mom might still have that button somewhere.

You already know that my parents used to hide destinations from my brother and me. They also made sure that our Easter bunny, named E. Bunny, hid Easter baskets and left abundant and truly perplexing but hilarious clues for us everywhere. (I should also add that my father, from whom I got my particular sense of humor as well as my awareness of my periodic, blinding gullibility, once convinced me that the Cadbury bunny really did lay those eggs. I had protested that bunnies don't lay eggs. When the commercial came back around again--and I'm certain that we were sitting on that rust-colored leather sofa--he said, "Now just watch." Indeed, the rabbit clucked, got up, and had laid an egg. How could I argue with the evidence of my senses?)

I think my father was the first person to notice that I was becoming a night owl, back when I was in high school. Once, when his mother was about to visit us and was going to stay in my room, he decided that I shouldn't get bounced out of my bed. I remember his telling me that it was important that I should be able to stay up and do my reading and writing in peace. I also remember his coming into my room early some Saturday mornings, while I was still sleeping, and making a space for himself to sit down between me and the edge of the bed. Usually, it was around 6:30, which is late rising for my father. And he would talk to me, about anything and everything, until I was awake, though still drowsy, and would get out of bed and come sit with him while he redesigned or streamlined processes or invented machines with Anvil. I do like my sleep, but I like spending time talking with my father more.

One winter, I wanted very badly to drop out of college and become a burger-flipper (not out of anything like caprice, or reckless love, or anything exciting like that, trust me). My parents wouldn't hear of it and brought me back to school at the previously scheduled time. I did what I could to get them to stay as long as possible, but eventually it was just time for them to make the trip home. After I got myself settled back in to my room (that was the year I lived in the basement), I got myself ready for bed. When I slipped into my bottom bunk, I realized that somehow, without my noticing, my father had stuck a little slip of paper into the springs directly over my head--a sheet from his omnipresent pocket notepad, marked with his signature smiling face, a sketch I would have to show you in order to have you be able to envision it. (We used to draw this face, and bellybuttons, on fish and bunnies too.) I left that face to look down on me from the mattress springs for the better part of the semester.

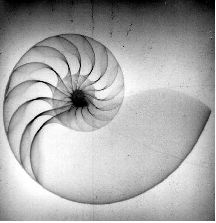

One of the things I love most about my father is that he is the most fearlessly creative person I know. His visual sense is incredible; he started taking photographs and learning darkroom technique when he was about eleven, if I remember correctly, and even his early stuff is beautifully done. He is a mechanical genius; I have watched him create whole processes from start to finish, from scratch. He continues to innovate even in the face of opposition or (what's possibly worse) blank indifference. And he figures out ways to help people around him figure out their reasons for being here, the things that will ensure that they have something to love, something to do, and something to look forward to. My father taught me much of what I know about how to treat other people well, with dignity and respect; through the way he has always treated my mother (he had her at that button, you see), he showed me the worthy struggle and boundless joy a healthy, strong partnership can be.

Part of the reason I'm thinking about my dad today--I mean, other than the fact that I think about him every day--is that he always wanted me to be a Supreme Court Justice. He wanted me to be the first female Chief Justice, in fact. He still thinks that Constitutional law could be my field. (I think, actually, that psychotherapy could be. Sometimes we disagree about my future.) I don't know if he was right; I do know that he never tried to foist that dream on me, that he never asked whether a doctorate in English would really repay the effort. In other words, he made sure that I could be fearless and creative in my adult life--that I could find my own big dreams and carry them out. And for that, I wish him all the Harley-riding his heart desires.

He's that cool.

sources for today's images: 1) Solo Regalos; 2) Amazon.