One of the things I miss about being in love is feeling that I'm the girl apostrophized in the happy songs. Instead, I find myself back in the melancholy ones--in the wistful verses, the grim choruses, the minor keys. In Michael Stipe's intoning that the one he loves is "a simple prop to occupy [his] time." In Dar Williams's crooning to a person who hasn't yet shown up for her life's big show, "There are times I think of you / saying 'Hey, that's beautiful; yeah, I see it too.'" In any one of Aimee Mann's sublimely wounded songs of frustration and disappointment; tonight, I'm thinking of "There's no charity in you / and that surprises me." And in my all-time favorite, Paul Simon's painfully defiant declaration that he has his books and his poetry to protect him: "If I'd never loved, I never would have cried."

One of the things I miss about being in love is feeling that I'm the girl apostrophized in the happy songs. Instead, I find myself back in the melancholy ones--in the wistful verses, the grim choruses, the minor keys. In Michael Stipe's intoning that the one he loves is "a simple prop to occupy [his] time." In Dar Williams's crooning to a person who hasn't yet shown up for her life's big show, "There are times I think of you / saying 'Hey, that's beautiful; yeah, I see it too.'" In any one of Aimee Mann's sublimely wounded songs of frustration and disappointment; tonight, I'm thinking of "There's no charity in you / and that surprises me." And in my all-time favorite, Paul Simon's painfully defiant declaration that he has his books and his poetry to protect him: "If I'd never loved, I never would have cried."

One fall, when I was in the middle of a situation whose idiocy never fails to startle me when I think back on it, I was visiting my beloved Brooklynite and put one of her Simon and Garfunkel CDs on as breakfast music. As "I Am a Rock" started, she turned to me and said, "It's supposed to be ironic." I'm never so sure about that, which is why she felt the need to remind me. In a sense, I can chart where I stand on matters of the heart through my responses to this single song. My relationship to building walls and fortresses is more nuanced now than it was a half-decade ago, I think, and I'm never going to get on board with abjuring friendship's laughter and loving the way that Simon does before tapering out to "And a rock feels no pain, and an island never cries." But I still feel the pull toward shielding myself in armor and deciding to let a whole class of slumbering feelings and sleeping words lie--if only so that I don't have to go through the self-indulgence of sorrow over and over again. I think that I have more creative ways to use my energy, frankly. But for someone who acknowledges her rudimentary and illogical belief that something about the world's organization implies directions if we just pay attention enough to see them, I find myself startlingly reluctant to follow some striking ones that keep showing up. For instance:

When I came home this evening, I came upstairs to change out of my teaching clothes and into jeans for the grading vigil I'm going to have to sit for much of the night. I decided to check in with 365 Tao, a funny little book I picked up at one of Ithaca's used bookstores, early in my graduate school career. Part of what makes the book funny (in a sad way) is that it's inscribed to a daughter from her mother, and yet it ended up on a used bookstore's shelf; I've always imagined it as having been a gift to some Cornell undergrad who flipped through it, rolled her eyes, and sold it a few days later. It's not the most poignant version of this scenario I've encountered, either: once, in Chicago's O'Gara and Wilson's (which is back in my active memory, following last night's post), I found a copy of the Johnson selection of Emily Dickinson's poems, Final Harvest--in its old design, the lovely cream-colored paperback with the tiger lilies on the cover. Inside the front cover was a beautiful inscription from one lover to another. And the book was on the "Recent Arrivals" table; I wondered whether the break-up had also been a recent arrival. Early in his massive novel Vanity Fair (1847-8), William Makepeace Thackeray comments on the satires that letters inevitably become: "Vows, love, promises, confidences, gratitude, how queerly they read after a while! There ought to be a law in Vanity Fair ordering the destruction of every written document...after a certain brief and proper interval.... The best ink for Vanity Fair use would be one that faded utterly in a couple of days, and left the paper clean and blank, so that you might write on it to somebody else" (ch. 19). It's possible that I never feel the truth of this sentiment so clearly as when I encounter a discarded or sold book that's been inscribed lovingly for its former owner.

The trick of 365 Tao is that it has one entry per day, with an index to let you know the days to which different entries are keyed. For as long as I've owned it, I've used it as a kind of horoscope, which seems a bit strange to me, sometimes, because the entries never change, making it a weirdly static kind of fortune-teller. Some years, I go eight or nine months without looking at it once. Usually, it just cracks me up.

Tonight, the two facing pages that confronted me were "Celibacy" (for March 1) and "Sorrow" (for March 2).

Seriously, maybe this confrontation wouldn't have felt quite so much like overkill had I not already spent the early evening finishing (for the fourth or fifth time) Rebecca West's devastating The Return of the Soldier (1918), whose ninety pages reveal, bit by painstaking bit and layer by tooth-gritting layer, the unfathomable depth of its narrator's loneliness. At one point, looking over a stream banked by gold and green mosses, describing her wooded surroundings in exquisite detail, she dead-ends unexpectedly in an understated lamentation: "The sight of these things was no sort of joy, because my vision was solitary." I hit that page at 5:30 p.m. and the 365 Tao pages at 6:45 p.m. Perhaps I should take a hint.

But, as West's narrator explains a few pages later, "A lonely life gives one opportunities of thinking these things out." I bear around with me this complex of pride and independence and solitary happiness and loneliness and longing and sad resignation. I've been with it most of my life. It is my familiar, the Grudge to my Vendetta. I know its contours with all of my senses, its smells both sweet and acrid, its feel angular and inviting, its taste delectable and ashy. I know the way it sings in my ears like the sea in a shell. I know the way it puts its hand at my back as a goad and a caress. It would, I suspect, be the omnipresent third party in the room, were there ever a somebody who stuck.

And it's not such a lonely life, the bulk of the time, though it is an intensely solitary one. I don't identify fully with West's narrator; she and I part ways when she declares, "Independence is not the occupation of most of us." In a sense, I think independence has always been my occupation, because, plain and simple, I refuse to mess around, to suffer fools lightly, to play any more games with my heart than I can help.

I was horrified when I first saw the movie Igby Goes Down (2002), because at one point "Igby" Slocumb receives a copy of Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet as a graduation gift and his character and the movie as a whole join forces to deride it, to turn it into a cliché, an idiocy, a overly romantic and utterly negligible nothing. Only a few months before I saw the movie, I'd been on the giving end of precisely that scenario: because Rilke's slim book has been such a touchstone for me, I'd given a copy to a then-somebody (you will recall him as the person who cranked off at me about bourgeois house renovation), thinking that it would prove a way to tour him round some of my emotional furniture. I went out of town to a conference and e-mailed home to see how things were going. "I'm reading the book," he wrote back. A couple of days later, he let me know that it was too full of advice, that maxims weren't much to his taste. (He thought Igby Goes Down was a good movie, too, so go figure.)

I have regained my unabashed love of Rilke's book. It's true that it's full of things that can be used as maxims. It's true that it could be overused as a graduation gift. It's also true that its doctrines are far tougher and more ascetic than the wrong reader might be able to appreciate. For those of you who don't know it--or who, God forbid, only know it through a crappy, faux-deep movie oozing hipster irony--Rilke's text comprises ten letters he wrote between 1903 and 1908. When their correspondence began, the "young poet," Franz Kappus, was 20; Rilke was 28. (When I first read this book, I was 19; the person who had recommended it and whose spirit still animates it for me was 64. I was on an airplane, flying to London, when I started it; I was on a train, speeding into the impossible green of the southwestern English countryside, as I continued it; I was in my cinder-blocked, orange-carpeted dorm room, with a view of green hills, hedgerows, sheep, and cows, when I finished it.) Two days before Christmas, in their first year of writing, Rilke reassured his young friend:

[Y]ou...are bearing your solitude more heavily than usual. But when you notice that it is vast, you should be happy; for what (you should ask yourself) would a solitude be that was not vast; there is only one solitude, and it is vast, heavy, difficult to bear, and almost everyone has hours when he would gladly exchange it for any kind of sociability, however trivial or cheap, for the tiniest outward agreement with the first person who comes along, the most unworthy. . . . But perhaps these are the very hours during which solitude grows; for its growing is painful as the growing of boys and sad as the beginning of spring. But that must not confuse you. What is necessary, after all, is only this: solitude, vast inner solitude. To walk inside yourself and meet no one for hours--that is what you must be able to attain.

Five months later, Rilke reassured Kappus again, in his inimitably bracing way:

And you should not let yourself be confused in your solitude by the fact that there is something in you that wants to move out of it.... Most people have (with the help of conventions) turned their solutions toward what is easy and toward the easiest side of the easy; but it is clear that we must trust in what is difficult; everything alive trusts in it, everything in Nature grows and defends itself any way it can and is spontaneously itself, tries to be itself at all costs and against all opposition.

By the end of summer 1904, Rilke was continuing to help Kappus build a bulwark against despair, a bulwark that wouldn't also cut him off from feeling:

But please, ask yourself whether these large sadnesses haven't rather gone right through you. Perhaps many things inside you have been transformed; perhaps somewhere, someplace deep inside your being, you have undergone important changes while you were sad.... If only it were possible for us to see farther than our knowledge reaches, and even a little beyond the outworks of our presentiment, perhaps we would bear our sadnesses with greater trust than we have in our joys. For they are the moments when something new has entered us, something unknown; our feelings grow mute in shy embarrassment, everything in us withdraws, a silence arises, and the new experience, which no one knows, stands in the midst of it all and says nothing....

[T]he sadness passes: the new presence inside us, the presence that has been added, has entered our heart, has gone into its innermost chamber and is no longer even there,--is already in our bloodstream. And we don't know what it was. We could easily be made to believe that nothing happened, and yet we have changed, as a house that a guest has entered changes. We can't say who has come, perhaps we will never know, but many signs indicate that the future enters us in this way in order to be transformed in us, long before it happens. And that is why it is so important to be solitary and attentive when one is sad: because the seemingly uneventful and motionless movement when our future steps into us is so much closer to life than that other loud and accidental point of time when it happens to us as if from outside. The quieter we are, the more patient and open we are in our sadnesses, the more deeply and serenely the new presence can enter us, and the more we can make it our own.... And that is necessary....

How could it not be difficult for us?

Indeed. As ever, even when my consciousness of it slips, I am more committed to the difficult labor of being this self, now, even if I don't know what all the difficulty is about, now, than I am to conventions and narratives I not-so-neatly side-stepped years ago. "Patience is everything!" Rilke exclaimed to Kappus in April 1903. "Love your solitude and try to sing out with the pain it causes you," he urged in July 1903. And in May 1904, he laid out the theory that has shaped my understanding of how the heart should work (even more than did Louisa's "Much More" from The Fantasticks, the song that made me want to be the kind of girl designed to be kissed upon the eyes): "Love consists in this: that two solitudes protect and border and greet each other."

Indeed. As ever, even when my consciousness of it slips, I am more committed to the difficult labor of being this self, now, even if I don't know what all the difficulty is about, now, than I am to conventions and narratives I not-so-neatly side-stepped years ago. "Patience is everything!" Rilke exclaimed to Kappus in April 1903. "Love your solitude and try to sing out with the pain it causes you," he urged in July 1903. And in May 1904, he laid out the theory that has shaped my understanding of how the heart should work (even more than did Louisa's "Much More" from The Fantasticks, the song that made me want to be the kind of girl designed to be kissed upon the eyes): "Love consists in this: that two solitudes protect and border and greet each other."I'm too much an idealist not to believe that somewhere, some other solitude is growing and waiting to be greeted. I hope it's only as painful as he can sing out lovingly.

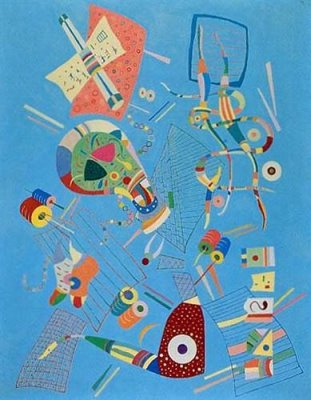

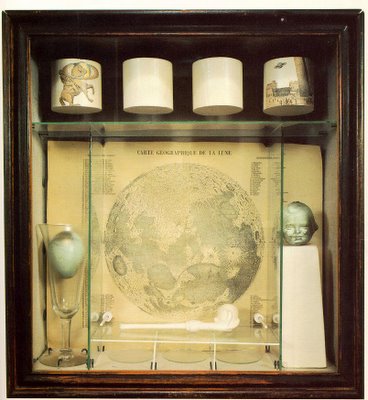

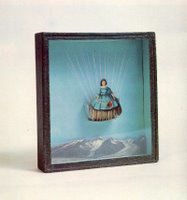

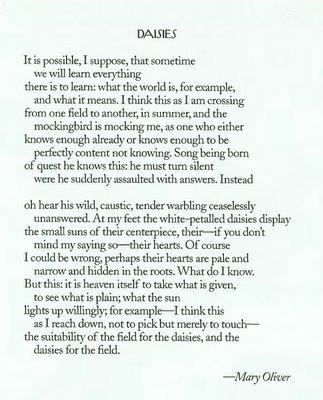

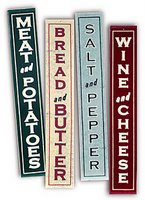

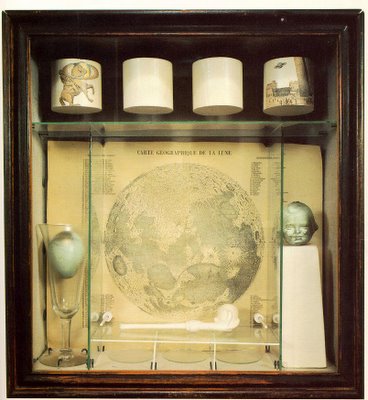

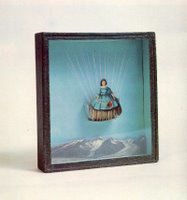

source for tonight's images: Joseph Cornell's "Toward the Blue Peninsula" (1951-2), "Untitled (Soap Bubble Set)" (1936), and "Tilly Losch" (c. 1935) all come from the WebMuseum.