The April fool's joke here, of course, is that this post didn't go up on April 1 at all. But I'm putting it up as if it had gone up yesterday not only because I was actually planning to do it yesterday (but then ended up not coming home from the furry beasties' house to write it out) but also because I don't want my April archives to be missing a day right off the bat. I have to say, though: I waited for the March 31 / April 1 changeover, wondering whether we'd go out of March like a lion or like a lamb. I was hoping that the end of the month would shed some light on how to interpret its beginning. But we came into March in a pretty middling way, and we've gone out of it in a fairly middling way as well--some flowers blooming, some cool breezes, some misty rain. My feet are still cold in the shower, mornings, even if I can go outside without a coat now. So, what I've concluded is that this year, that old adage applies not so much to meteorology in my world as to workload and emotional state. March came in with a stretch of (relatively) peaceful workdays, days when I could get some high-quality emotional reflection and prose-crafting done in the evenings--which was necessary, since March also came in with some high-quality emotional drama, as you may recall even though you only heard it obliquely. But though March went out with a lowered degree of emotional tension (recall that it was exactly a month ago that I railed my way back into embracing my solitude), it also left in its wake an unprecedentedly high level of professional overload, about which I think I'll say no more here, chiefly because I have what I think are more interesting things to talk about.

Namely, personal ads.

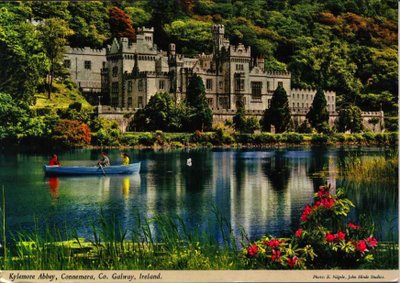

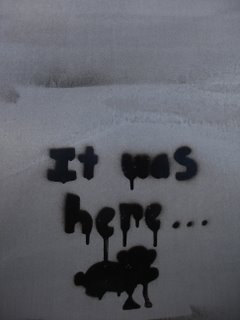

Those of you who have been with me since the beginning of this Cabinetry, or who have valiantly read your way through all the archives (whose extent surprises me no less than you, I'll add), will recall the utterly inspired graffiti that I discovered on the village mailbox, back in August. Just in case you don't recall it, though, here it is again. I'm happy to offer it a second time because I love this image so much.

Back on that December afternoon, I showed you this picture with a semi-secret frisson of hopeful joy because I was about to go on my first date with someone I'd met through my first foray into online personal ads, with which I rapidly became obsessed at the end of last semester because they're such a strange genre of self-representation. And yeah, okay, because I thought maybe I'd find love that way. Even though I felt mighty silly and not a little skeptical about trying to encapsulate myself in a series of answers to a series of strange and not-so-strange questions ("The celebrity I most resemble..." was one I skipped, just for instance, having decided that ignoring the question was a better way to belittle it than to do what so many people do, which is to write "What a stupid question"), I'm also enough of a romantic and enough of a narrative scholar to appreciate a well-turned story's arc. Part of me still falls for the narrative trajectory of fated love every time it rears its head. And this is, in large part, why I've started thinking of this narrative arc as a "girl meets blog" story; I entered into the personals game thinking I'd find a somebody. Instead, it turns out that my writing was out there waiting for me to show some interest in it again, and now I'd say we're in a pretty mutually enriching relationship.

But I'm focusing on the self-representation part of personals today. And alas, this writing, like so much of what I'm doing these days, is going to be more attenuated than I'd like. (So much for my confident claims of mutual enrichment. Right now, I am someone distressed by having to spend so much time away from a lover she's just gotten a chance to start getting to know. Everything is still bright and possible, but I have to sequester myself away for most of every day. We'll see whether we get sick of each other when I have more quiet and settled time to work myself into a writerly ferment... Maybe I'll get to have some tantrum-laden fights with my own words. Wouldn't be the first time.)

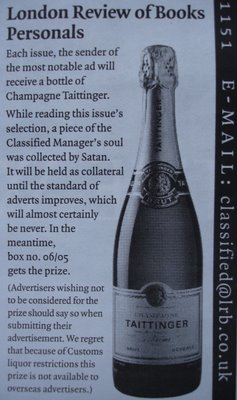

One of my colleagues recently hooked me up with a one-year subscription to the London Review of Books, a periodical I'm overjoyed to be receiving not because of its essays and poems (though, you know, those can be kind of useful and interesting too) but because of its personal ads. When I first moved back to Gambier, one of my favorite ways to try and repay my marvelous friends for feeding me great dinners while I was settling in was to do dramatic readings from the LRB personal ads. It's a game that to my mind never gets old. One night, another couple of friends were dining with us, and I mentioned how much I love the LRB ads and how much they make me want to make an outlandish one up and submit it, just to see if anyone would respond. (Keep in mind that this was a good eighteen months before I actually capitulated and tried a personals venue myself.) "Do you actually think that most of those ads haven't been submitted for exactly that reason?" the husband of this couple said to me. I'd never thought of it that way before, of course, because I prefer to believe that my funny or bright ideas have never occurred to anyone else. But now when I do the readings (mostly to myself), I approach them with a greater kind of readerly tension; I'm suspended between a couple of possibilities for thinking about what they might mean. (And no, I don't think I'm reading too much into these. They're obviously made to be read into. Follow along.) Here are my favorite three from the 23 March issue:

I like several things in these ads, which come from the same positioning on the page as the last three that I gave you, back on the Ides of March (when, fortunately, there was not much need to beware). For one thing, the person seeking love in the top ad in both of these groups is done with loons. For another, the person in this week's top ad notes an important (though not always fixed) distinction between courting and writing: "she wants romance, not a pen pal." I love that the guy in the middle kicks off his ad with what (as a result of some quickie iTunes-based research) I think is an allusion to the song "This Wheel's on Fire," which was recorded by The Band (with and without Bob Dylan) (which in turn leads me down an entirely different road of knowledge I don't possess). But what I hear in my head when I read "This wheel is on fire" is the beginning of the James song "Laid": "This bed is on fire / with passionate love." This James song, in turn, could lead to an entirely different road of reflection on romantic obsession, but we'll perhaps go there another time when, for instance, there's more time for it.

And I super-love the woman at the end (who lets us know she's female by means of that great declaration "I am a woman"), whose "Now you" conclusion really brings to a head the several tasks she's already laid down for me, not least of which is to look up "peristerophobia." Peristerophobia, it turns out, is not in the Oxford English Dictionary. (If I sent it in for them as a possible word for the third edition, which is still underway, would I give them this personal ad as its 2006 source? Would they use it?) But "peristeromorph" is in the dictionary and lets me know that the ancient Greek word for pigeon was (transliterated, of course) "peristera." Peristerophobia is a fear of pigeons, something I can kind of understand, having had my food menaced by flocks of impertinence on several occasions. I also love that this woman's ad makes me remember the Halloween party I attended in graduate school where a younger student dressed up as Jean Genet (prison garb was involved). When I asked him who he was, he slurred "Zhanzhenay" at me. I asked him to repeat it. He slurred it again. I gave up, figuring that my brain would make syntactic sense out of those sounds later on, which it did.

Basically, then, what I'm saying is that I love these ads for the way their details mirror me and my mind's motions back to myself . But I also love the way each of these people has managed to make a little image of him or herself. Bachelor #1 is using that age-old fake-out of speaking about her "friend" in order to talk about herself and a series of frustrations she's had in the past with pervy loons who like to list their medical conditions and thus (and maybe in some other ways, too) do not qualify as strong or sorted, and my guess is that she's maybe had a bad or at least frustrating experience with long-distance relationships. Bachelor #2 is a scientist HTM (hoping to meet--see how I can talk the lingo?) a woman who's maybe also a scientist, and he's OK with someone a little older than he is, possibly because he has subordinates at work and doesn't need another subordinate in his love life (that latter is just my guess, based on the idea of the underpaid assistant's being on fire). In fact, he maybe is looking for someone older who will start straightening him out from past mistakes, because he is (note the pun, which is pretty good) a "perennial misfiring love jerk." Bachelor #3 wants you to know that she's a woman who knows what she wants and isn't afraid to let you know it--right down to the fact that she tells you she'll tell you ten things you should know about her but then tells you eleven. And she wants you to know that she knows her shit: she loves the "aphrodisiac" M&Ms best; she smokes the toughest cigarettes. And she wants you to be monied, though she might feel wistfully that she wants to add you to her collection even if you make under £80,000 a year.

Yesterday, when I went into the village to get my mail, I stopped by the bookstore and discovered a new pile of junk on the clearance table in the back of the store. In one of the plastic baskets back there were a bunch of packages of tape flags reading "RUSH." I imagine all of these personal ads as being invisibly tagged "RUSH."

On the other hand--and this is where the readerly tension comes in--I also imagine them as competing for the other prize to be gotten from advertising in the LRB:

Which, it should be noted, Bachelor #3 won.

Meanwhile, reading the champagne-prize announcement copy has made me revise my LRB personals aspirations in a way that feels perfectly apropos. Now, I no longer want to make up an ad and see who answers it. Instead, I want to get a job as the Classified Manager in Charge of Personals. In my head, I hear Clementine from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind saying "Someone has that job," even as the skeptic in me voices Joel's doubt that anyone could. I'm sure that running the LRB classifieds is a job that often sucks a lot. But surely, processing each issue's personals must be something to look forward to--even figuring in the pain of having a piece of your soul collected by Satan when advertisers slack off.

I made it about four months on the personals site, myself, before the epiphany that revealed to me the fundamental error of my ways. By the end, I was having the opposite reaction to that which I desired. Rather than feeling relief that there were so many single people in central Ohio--since here in my village home, we're a pretty big and sometimes aggrieved minority--I started feeling staggering overload.

Remember that Marvelettes song "Too Many Fish in the Sea"? I learned that song from the soundtrack to The Big Chill when I was about ten. There's a lot of good anti-mediocrity / anti-settling sentiment in it, particularly in its conclusion: "I don't want nobody that don't want me / (Cause there's too many fish in the sea) / Ain't gonna love nobody that don't love me / (Cause there's too many fish in the sea) / I don't need nobody that don't need me..." "Bait your hook and keep on trying," these women urge us. But the personals pool started feeling a lot more like a story that a friend told me over lunch on Friday. He was in Brooklyn early in March and went to a fishmarket with his son and his son's girlfriend. The fish vendors would, as fish vendors seem to do all over the place (which makes me wonder even more ruefully how it is I've never managed to see this spectacle), throw customers' chosen fish over to someone else, who would gut and package the fish and then throw it back. "It was a pandemonium of fish!" he said to me. I love that.

I tell you, the personals site had become a pandemonium of thrown fish. And so, for now, I'm more than happy to sit back and watch how others bait their hooks.