This morning, I dreamed that the rain would not stop. It rained and rained and rained, water falling in thick ropy streams off my gutterless roof, until (looking out a window with my companion, whoever that person was) I said, "See how it rains? We're going to have a flood." Rapids were forming in my front yard. I was back in the house in North Vernon, the first Indiana house, standing at the window in my parents' bedroom, watching the yard fill with water, while the rain fell unceasingly. The rain would not stop.

Other things happened in the dream, things I may even have meant to tell you about, but that's the image that left a mark.

On Thursday evening, we had a tornado watch, and a thunderstorm so strong it bent my friends' forsythia bush over my car while we ate dinner and watched our movie and hockey game (or perhaps I should say: while we ate dinner and then my friends watched things and I fell self-flingingly into sleep and then did my bit to help my old dog friend to sleep, as well). When I arrived at the house, my friend was standing in front of her television and said, "There's a tornado warning." That last word, coming in instead of "watch," made everything different for me until I could confirm that the warning was in another county. "Tornado warning" is a phrase, I was reminded the other night, that mobilizes me, strips away every thought but that of preparing, descending, waiting, hoping.

For those of you who aren't from tornado-rich areas (like my students, who asked when the disaster siren went off at noon during our second week of class, "What should we do if it ever is a tornado?" and thereby earned themselves a lecture on tornado safety): A tornado watch means only that conditions are favorable for producing a tornado (whether suddenly or gradually). A tornado warning means that someone has spotted a tornado--it's in play and is being tracked and could be coming your way. In a tornado watch, one stays vigilant, checking the weather on a regular basis, recalling where to go in the building should something be spotted somewhere. In a tornado warning, one goes into a basement or, if there is no basement, into an interior space with no windows; the goal is to get as low and as centrally located and windowless as possible.

Now, I am known as something of a catastrophist in my family, I think; I have long been the one among us four most likely to believe that disaster is imminent and something to be taken seriously. I am the one, then, who noticed the weather icon in the corner of the television screen turn red and tornado-shaped, the day after Thanksgiving a couple of years ago, and I am the one who insisted we go to the basement, as soon as we confirmed that there was indeed a tornado warning on for my family's town.

It's possible that I would take tornadoes less seriously if I hadn't been schooled in them so rigorously by southern Indiana school systems. One of the first things I learned when I arrived in southern Indiana, midway through second grade, was what to do during a tornado drill; in fact, tornado drills were what I talked about when I visited my old class in East Amherst the next June. I demonstrated the position we all had to assume in the hall, into which we'd filed quietly and quickly: on the knees, facing the wall, head to the floor, textbook over the back of the neck and base of the skull. Avoid the hallways that are wind tunnels. Keep your eyes and mouth covered to protect yourself from broken glass. Get to the first floor, if you're in a multi-floor building. (I do not remember what we did in our nearly condemned junior high school, before my family left for a different town and district; I suspect I always believed that in a real tornado in that school, we'd all die, and thus any memory of our drills there have gone into the repression bin.)

In 1986, I read Ivy Ruckman's Night of the Twisters in conjunction with the Young Hoosier Book Award; even then, I was a sucker for books on lists. In 1985-6, I read nearly all of the YHBA nominees, on both the intermediate/elementary and advanced/middle school lists. In 1986, I must just have bought Ruckman's book from one of our Scholastic book order pamphlets; even then, I was also a sucker for buying more books than I'd planned to, always the kid with the biggest stack, always the one who bought the most discarded textbooks when the school sold them to us for $.25 apiece.

Night of the Twisters scared the bejeezus out of me, not least because of its vision of days without clean underwear. Why this particular detail should have bothered me so much more than the devastation of whole houses, I can only guess: I suspect it had something to do with knowing that, bereft of clean underwear (and, in turn but of less consequence to my ten-year-old self, of all other clean clothing), one would have to request such a very basic thing and thus would find one's dignity and personhood at the mercy of others.

That year, we watched a horrifyingly graphic tornado safety video in the school library. I also saw that tornado scene from Places in the Heart over and over again in the mid-1980s; I've never watched that whole movie, but I did learn from it that one should never accept a ride in a car from someone when the funnel cloud is bearing down.

Looming perhaps largest of all was the music video for Starship's "Sara," a song that plagued me in elementary school not least because of the video's traumatizing use of tornadoes. In this video, we get two narratives overlaid in farm somewhere on the plains, a location established with several Walker Evans wannabe shots of sturdy-looking depression-era farming family members, as well as some tractors and a barn, a tumbleweed and a dog. In the first, framing narrative, a tarted-up Rebecca De Mornay is running out on the massively mulleted lead singer Mickey Thomas in her red Chrysler LeBaron (or is that a Ford Mustang?) convertible. In the second, flashed-back narrative, a child (presumably the young Mickey Thomas, though this is chronologically confusing) loses an older woman to whom he is somehow affectionately bound, though it's never clear what their relationship is (is she his long-lost mother? is she an older woman on whom he has a childhood crush?). All we know is that she slides into this farming landscape in an enormous black sedan and sweeps him into her arms, and that later she rides off down their dirt road on a bicycle. And then that a tornado blows in and presumably kills her. The first, framing narrative is in color, the second in black and white, an obvious homage to The Wizard of Oz (whose tornado strangely never bothered me all that much).

The most disturbing thing about this video--even more disturbing than, say, the fact that Mickey Thomas may have fallen in love with the eponymous heroine of his video because she seems to be psychically tied to his long-lost older woman--is its double killing. For, at the very end of the video, as Rebecca De Mornay's Sara (who has vampily mouthed "I love you" in many home movie flashbacks during the video, before seeming to degenerate into a drunken party girl) charges off down the road in her convertible, the sky darkens and super-fake looking dry-ice-fog clouds come blowing in. She too will die in a tornado, we're left to believe. I think the lesson I was supposed to learn from this video, when I was ten, is that women should stay in their unobtrusive, unflashy places (and should never, ever cheat or leave)--or else they'll die in tornadoes.

Fortunately I didn't pay much attention to that part of the lesson.

The other thing I learned from seeing that video over and over again, though, is that tornadoes make an ungodly mess: the video features roofs being picked up and buildings being crushed by flying, falling objects. When it's all over, you can understand why everyone looks so stricken.

I suspect that the lack of a basement in the house in North Vernon was part of what always terrified me about tornadoes. We had a central closet where we probably all could have fit, and it was certainly windowless, but all we had under the house was a very shallow crawlspace. I ran into a difficulty somewhat like this one when I lived in Ithaca. There, I had a basement, but it was a good half-foot shorter than I, and it had a dirt floor and a significantly creepy feel. Horrors could have happened in that basement. I used to wonder whether I would actually have gone down into that basement, had we had a tornado warning while I lived there; there were windows in the basement, and it would have been one hell of a place to die.

By the time I lived in Ithaca, I had actually seen two tornadoes in person--except that they were out over a gulf and thus were waterspouts. That was the year I started packing a shoebox of possessions I wanted to be sure to have with me if a storm actually hit. Because I had just finished junior high (for we were on vacation that summer when we saw the waterspouts, which actually did significant damage not far from where we were), those possessions I deemed important were things like my Walkman and my favorite tapes, my deck of cards, a couple of key notes from important people, a small framed picture of the person I had had a crush on for months, a t-shirt, and clean underwear. I packed all of this stuff into the black and yellow Capezio shoe box my jazz oxfords (purchased for pipe organ lessons) had come in, and I had the box ready to go at a moment's notice, the second a warning hit. I think I packed a similar box for more severe-feeling tornado watches for the next couple of years. I don't remember what made me stop. I now know, of course, that clean water would be more important to me than clean underwear, and that it's absurd that flashlights were pretty much never in my emergency arsenal.

The amazing thing about the two waterspouts (which we saw on the same June day) was the way they focused and pulled water around. From shore, we could see the cloud of whipped water pouring upward at the spout's base; it looked like a symbiosis that could go on forever, this long, dark, grey chute tying and turning cloud to sea to cloud. I was so enthralled that I took pictures--or at least didn't protest when my father took pictures. Now, I'm not even sure whose pictures they were. But they were extraordinary, and it is indeed possible that my little camera was part of my emergency box, as well. You might not believe me if I tell you that the box didn't contain any books. But I think that it might be true; that was the year of making a half-hearted effort at being cool.

In the end, Thursday night's tornado warnings were three counties away and didn't threaten us at all, though I did learn this afternoon that one of my colleagues has a son who called her on Thursday from a neighboring college, where he was staying for a program, to ask what to do since he and his friends could see branches flying around outside; tornadoes touched down in that county, though fortunately not where he was. (She talked him through the tornado drill and he got everyone into the dorm basement. "I saved his life by remote control," she joked.) When the stormline reached us, the trees thrashed and dipped, and the rain pounded the ground and clouded the sky. We patted the dogs and waited for the power to go out. But the power stayed on, and the storm kept on going.

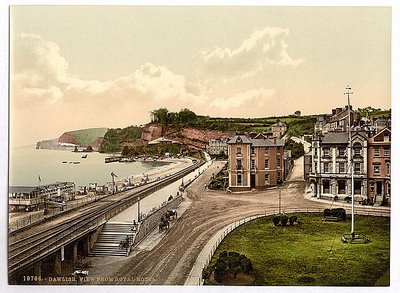

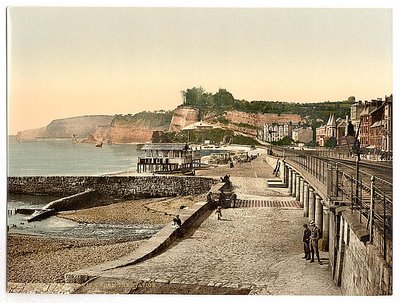

source for today's images: the NOAA (the first picture is the oldest known photograph of a tornado; it dates to August 28, 1884).