This morning, it occurred to me that you might not have the foggiest idea of what I'm doing down here at bibliography camp. Here's the short overview: my current research project centers on how a certain body of auto/biographical (that slash signals autobiographical + biographical + the things that are a little of both) texts got put together, and I decided toward the end of my dissertation work that it would be a mighty good idea to get some actual, professional training in how to study printed materials, at some point. That point is now. I'm enrolled in a week-long descriptive bibliography course, in which I'm learning how to pick up a book from either the hand-press period (i.e., c1500-c1800) or the machine-press period (c1800-present) and write down a detailed description of its format, collation, signing, and pagination. There's a lot of other material to describe, of course, but this course is the introduction, and so we stop short at pagination and a little bit of transcription (copying out what's on a title page).

These words may mean nothing to you, and so let me practice what I now know and explain myself. When I'm handed a book in this course--and we're actually handed boxes of six books for each night's multi-hour homework session, which comes fast on the heels of our six hours of lab, museum, and lecture during the day--the first thing I do is start nosing around in the opening pages, trying to ascertain what the book's format is. In bibliography, to determine a book's format is to determine the relationship of the book's gatherings, or folded and stitched pages, to the sheet of paper on which that gathering was originally printed. In the hand-press period, in particular, books were printed on sheets, folded, and quired or gathered. Those gatherings then got stitched together into books; after the stitching, they received some kind of binding, though at that stage things get complicated and beyond our purview this week. There are a few very basic formats. If a sheet has been printed and then just folded in half (imagine the way a greeting card is printed and folded), the book's format is called folio, and we say it has two leaves (each leaf having two pages). If it has been printed and then folded twice, it's a quarto (four leaves, eight pages). And if it's been printed and folded three times, it's an octavo (eight leaves, sixteen pages). If I didn't have class again in 40 minutes, I'd draw you some pictures. For now, take my word for it (and go out looking for diagrams on the web, if you're super-curious). There are all kinds of ways to determine format. Some of the coolest involve looking at the chain lines (the lines left on a sheet of paper by the mold in which that paper was made), which go in different directions depending on how many times the paper has been folded; and looking at watermarks, which end up in different places on a leaf depending (again) on the number of folds. The more complicated formats are things like duodecimos, where there are twelve leaves; and things like sixteenmos and eighteenmos and twenty-fourmos. (We haven't had any from that last group yet, but I have a feeling my moment of reckoning may arrive in about four hours.)

Once I've determined format, I get to determine a statement of collation, which basically involves paging through the entire book, taking notes about its gatherings--where those units of two, or four, or six, or eight leaves are, and how they're attached together. As I've told a couple of people, here and elsewhere, this work is so simultaneously lively and methodical that I feel almost meditative while I do it. I have to keep my mind completely in the game, or else I'll miss the moment when I switch from gatherings of four to gatherings of two, midway through a book, and then switch right back. Or I'll miss the moment when the printer put the wrong signature on a leaf. Now, the signature of a leaf is the little number or letter that shows up somewhere in what's called the direction line on the page. Generally, it's going to be alphabetical or numerical; one gathering will be signed A, and then the next B, and so on. You may be able to find books in your own possession that display such signatures, especially if you have anything that's fairly old. Look in the center or the gutter (i.e., inner margin) of the bottom of the right-hand pages, and keep your eyes out for the alphabet, or for what looks like a weird, intermittent page number. That's your signature. Printers were not always so perfect about getting every number into a signature, which is where the fun comes in. This morning, for instance, I worked on a book that had two different signatures, one (numbers) for the groups of six in which the book was actually gathered and one (letters) that was obviously left on the printing plates from an earlier, larger format edition of this book. Sometimes individual letters will just go missing, or will get missigned. There's a whole grammar for writing this stuff out, and it looks remarkably mathematical, which is part of the reason I was having all those dreams about math before I came down here. (Now, I'm sleeping so happily exhaustedly that I wake up not remembering my dreams at all.)

I would offer you an example of a formula, but I don't think I have an option of doing superscripts and subscripts, which are everywhere in this stuff. So, you'll have to take my word for it: these formulæ read like a different language. I can show you one signing statement, which is just the string of symbols that alerts a reader to how each of a book's gatherings is signed--what the marks are that distinguish one gathering from the next. This part comes after a statement of format and a statement of collation, and a simple one looks like this: [$1,3 signed; signing $3 as '$*']. (This book, by the way, had gatherings of six leaves, which were signed with numbers rather than letters.) Translated, what that statement means is "the first and third leaves of each gathering are signed; the third leaf is signed with an asterisk added to the number of the gathering." On the page, this means that in the first six leaves (or twelve pages) of the book, which are all stitched together, 1 should be signed (but because it's the title page, it's not), and 3 is signed 1*. In the second six leaves, leaf 1 is signed 2 and leaf 3 is 2*. In the third six leaves, leaf 1 is signed 3 and leaf 3 is 3*. See?

As you who have taken languages may have experienced, learning a new language can be a continually epiphanic experience. At one moment this morning, I sat looking over a somewhat bizarre string of data I had assembled, and I had no idea what to do with it all. I sat and looked, sat and looked, and suddenly, the patterns came erupting into my mind, and I had the notation for them, too. One of my favorite experiences of these mornings has been recopying my messy pencilled ideas into neat, inked versions, just before we go to the lab where we work through our night's work. I am so pleased when I find out I've done my work capably and well. But I'm also so pleased when I find out just how I've done it wrong and can then fix my other errors before it's time to put another formula up on the lab's whiteboard and go to work critiquing it. In some sense, though, I'm an overly distractable bibliographer (which doesn't seem to be keeping me from rocking the house; yes, all of you "told-you-so"ers, you can tell me so when I talk to you again; I turned up here knowing just plenty, and knowing where to find what I didn't already know). I can't help but notice things on the pages that I'm working through, though I notice them in fits and starts.

Yesterday's title, for instance, came off an early page in a music book we were examining. Another book in that group, The Gleaner: A Miscellaneous Production in Three Volumes, By Constantia (1798), featured a character named "Flauntinetta," whose name ended up in the bottom corner of one page as a catchword, to tell the printer what needed to go at the beginning of the next page. So of course I couldn't ignore a catchword like Flauntinetta and proceeded to read, and then transcribe, the next page:

Flauntinetta, the long incorrigible Flauntinetta, became a widow; and both herself and children were totally destitute!! It was in the moment of her calamity, that the eyes of her understanding being opened, she consequently beheld the revered guardian of her youth, adorned with every virtue which can dignify humanity, and, once more sheltered under the maternal wing, she hath, at length, learned to estimate the value of rational tranquillity.

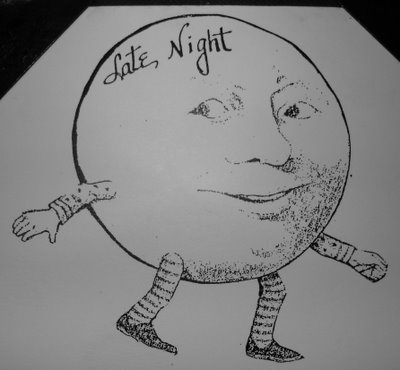

From then on, I picked up bits and pieces out of that book, as I picked through it, page by page, seeking out the details I actually needed for my homework. "Lucinda was her creditor." "Just returned from a tour of friendship." "The most rapt sensations rushed on my soul, while the poverty of words necessitated me to remain silent" (that's my favorite one). "The experience of every day evinces that humanity is subject to error." "but that pang was transient." I could offer you more pieces of text, but instead I will draw this writing abruptly to a halt (because it's time to go learn about printing) and tell you that the pictures scattered through this post are also things I've been gleaning from the books, now that I've gotten the all-clear from my lab instructor to take whatever pictures I might want. The guy at the top of the page was my sign, last night, that the books were winning and it was time for me to go to sleep; but this morning, his puckishness is so friendly that I know I misinterpreted him. (It is possible that I had not yet read the right books to interpret his looks.) The volcano in the middle, well, how can you not take a picture of a volcano when it shows up in the middle of a black letter volume? And I just liked this pair.

You'll undoubtedly get more book snippets from me before this week is out; my eye doesn't seem to want to stay fixed only on what I'm meant to see. In other words, I am seeing those things, plus all manner of others. And it will come as little surprise to those of you who know me well that I am utterly in paradise.